Anthony Dixon is a name that hundreds of women across the country will never forget – but for all the wrong reasons.

The once celebrated colorectal surgeon caused further injury to patients suffering with crippling pelvic floor and bowel issues, many of whom had turned to his expertise in times of desperation. This was a surgeon at the pinnacle point in his career, having developed what were deemed pioneering and innovative treatments in the form of Laparoscopic Ventral Mesh Rectopexy (LVMR) and Stapled Transanal Rectal Resection (STARR) to treat rectal prolapse.

Instead, he has since been dismissed from his position, his techniques are now marred with controversy, and his patients have been left maimed and living with chronic pain worse than pre-surgery, with many now in pursuit of claims for medical negligence. To add insult to injury, the people injured by Anthony Dixon’s inappropriate rectopexy treatment cannot access new specialist centres set up by the government to help victims of mesh.

What is the rectopexy mesh investigation?

From 2000 to 2017, Dixon was a colorectal surgeon at Southmead Hospital in Bristol, as well as the private establishment, Spire Bristol Hospital. In that time, he performed what he called ‘simple and straightforward’ surgical procedures on both men and women affected by prolapsed bowels, where the rectum either falls out of the anus or inverts back on itself within the body. To reinforce and reattach the rectum, Dixon’s procedures involved implanting surgical mesh into the body using keyhole surgery.

But Dixon became the master of his own demise by failing to ensure his patients made an informed choice in their treatment options and dismissing concerns they had. He was too quick to use his techniques without a second thought for any long-term complications.

Dixon was initially suspended in 2017 when concerns about his practice were first raised. He was eventually dismissed two years later in 2019. Dixon’s response was that his procedures were ‘all done in good faith.’ Yet he failed to appreciate the implications his techniques had.

An investigation into his practice by North Bristol NHS Trust found that 57 women out of 143 treated by Dixon should have been offered an alternative, non-invasive option before surgery. But this figure only relates to patients treated on the NHS. Around two-thirds of the operations he performed were private patients at Spire, so the true figure could be substantially more.

Following media coverage into the use of mesh to treat rectal prolapse and concerns raised about Dixon by North Bristol NHS Trust, Spire Healthcare decided to launch their own inquiry. They have since recalled 300 patients who underwent rectopexy to have a consultation with an independent specialist consultant surgeon at no charge to ask questions regarding their treatment and to establish whether or not they were experiencing any symptoms.

In mid-2019, Spire set up their own Clinical Advisory Group, consisting of four expert external consultant colorectal surgeons, with patients who had undergone LVMR being offered an outpatient appointment to identify any ongoing symptoms and establish any concerns surrounding the care they received.

Full figures and findings from the Spire investigation are yet to be released, but many have been advised to seek independent legal advice if they are contemplating a medical negligence claim. For more information about the mesh compensation claims see our dedicated Rectopexy Mesh Claims page. Patients who have since officially complained about treatment by Dixon have stated they had no knowledge of the procedure, that it was not what they expected, they did not give consent for the operation, or had complications post-surgery.

In the last 150 years, there have been few medical trials to compare the treatments for rectal prolapse and even fewer into the outcome. However, for a large proportion of Dixon’s clients, they were not told of alternative treatment options, let alone given the opportunity to decide on their care pathway.

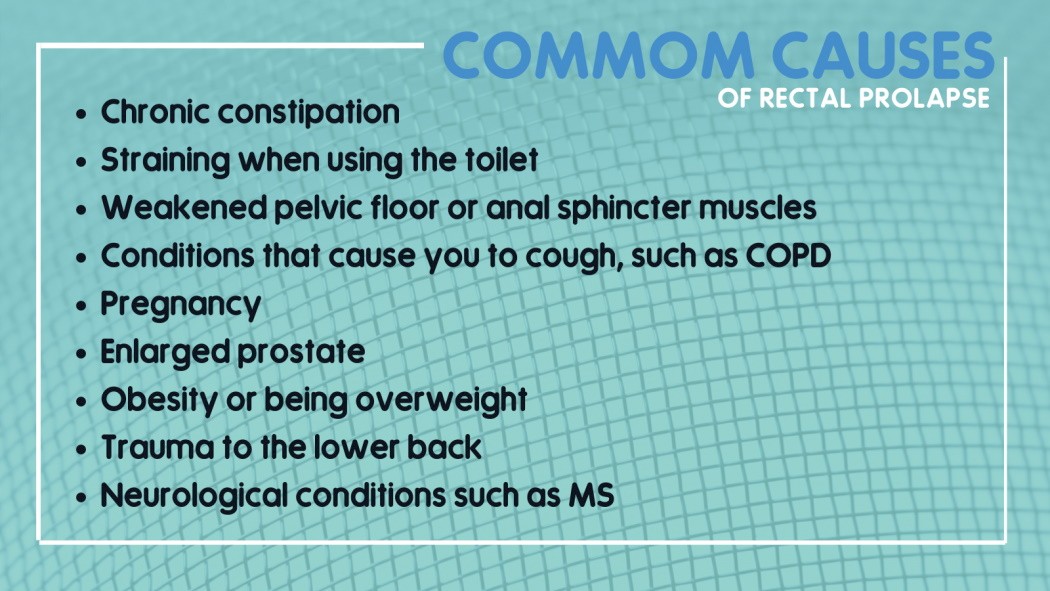

Things like diet and lifestyle changes can improve the constipation or incontinence experienced by those with a prolapsed bowel. Information and guidance can also be given to educate patients how to avoid bowel problems and how to irrigate the bowel to relieve symptoms. If symptoms are as a result of a weakened pelvic floor following childbirth, patients should be given information on the importance of doing pelvic floor exercises to strengthen the sling of muscles which hold in the internal organs to reduce their risk of prolapse.

What is mesh and what are the risks?

Mesh is used routinely in medical procedures to reinforce tissue, most often without issues. It is often used in procedures to repair hernias, rectal prolapse, or urinary incontinence. It is made from synthetic polymers or biopolymers, the same plastic found in ropes, carpets and plastic containers.

But when bacteria is present, particularly around the bowel and vagina, this can cause the mesh to erode, degrade or adhere to surrounding tissue.

The sheath of mesh inserted in the rectum has been found to have rolled up like a cigarette in many instances as a result of poor surgical technique combined with inferior quality tissue where the mesh was inserted.

In other cases, flesh has grown around the mesh, meaning it cannot be removed. Mesh has incorporated with a patient’s rectal wall, leading to tissue from the rectum eroding into the vaginal wall.

It also has sharp edges which dig in to surrounding soft tissue and nerves, sometimes causing obstruction and haematoma. In some instances, the mesh has pierced a patient’s bowel, leading to infection, risk of sepsis, and the need for a stoma.

Former patients of Dixon have been left unable to walk and needing a wheelchair, resistance to antibiotics due to prolonged and recurrent infection, or feeling like they have bits of broken glass lodged inside them. Although not proven, some patients with mesh have developed symptoms similar to those of autoimmune disorders, such as anaemia, rheumatism, fatigue and dry eyes.

In the most heart breaking of cases, one of his patients took her own life four years after she underwent surgery at the hands of Dixon. She had agreed to have rectopexy to avoid having a hysterectomy, yet Dixon removed her ovaries against her knowledge during the procedure as ‘they got in the way’. She sadly couldn’t live with the life-changing pain and reduced quality of life she suffered in the years following surgery.

Another patient was just 15 when she underwent rectopexy to treat a suspected bowel prolapse; seven years later she now needs to irrigate her bowels daily.

Is there a way to move forward for mesh victims?

Following a government review led by Baroness Cumberledge – the Independent Medicines and Medical Devices Safety Review - the use of mesh to treat urinary incontinence has now been suspended. A surgeon wanting to use this technique must show documented evidence that they have received additional training and have the experience to perform the surgery.

New centres for victims of pelvic mesh have also been created. Here, people have access to a colorectal surgeon, urogynecologist, urologist, chronic pain specialist, and physiotherapist for any future procedures or medical interventions.

However, rectopexy patients don’t have access to these centres. The complication rate of vaginal and pelvic mesh is almost ten percent, but for rectal mesh, nobody knows just how many procedures have been carried out or the complications that have arisen since.

Dixon is just one surgeon who performed these techniques. On the LVMR voluntary mesh registry, there are 95 surgeons signed up in the UK out of a total 749 specialist bowel surgeons.

Following publicity of the complaints made against Dixon, the National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) issued guidance in 2018 which said ‘Current evidence on the safety of [LVMR] is limited in quality. Therefore, this procedure should only be used with special arrangements for clinical governance, consent and audit or research.’

But this controversial surgery can still go ahead. Will patients who are given the option to have rectopexy in the future be able to make an informed choice unlike their precursors? This reinforces the importance of understanding all options available to you before you undergo any surgical or medical procedure.

Medical consent is a fundamental legal and ethical principle which underpins good practice and patients have a right to be involved in any decisions regarding their treatment or care. In 2020, the General Medical Council (GMC) published new consent guidance to help medical professionals understand how to meet their regulatory obligations regarding patient consent and decision making.

Hopefully, more awareness around informed consent will prevent future scandals such as mesh and rectopexy which have drastically impacted the lives of thousands of people in the UK.

The deadline for NHS complaints about Anthony Dixon has now ended, but as previously mentioned the Spire investigation is still underway. We are working with Spire clients who have received a letter following a review of their care to assess whether they have a claim to be made.

Consultant senior solicitor, Sarah Johnson, who is handling one of our Spire rectopexy cases, says one main concern is the length of time that it has taken for this review to take place.

“My client initially had surgery in 2008, but it was not until ten years later that concerns were identified. It has then taken a further three years for their CAG inquiry to reach a conclusion into her case. This will have just added to the distress and agony that she, like so many others, has gone through.”Sarah Johnson, consultant senior solicitor

There is financial, pratical and emotional support avaliable for mesh patients (men and women) who have suffered complications of mesh surgery.