Sports injuries have long been classified as ‘low priority’ for patients presenting at accident and emergency departments. But failure to recognise and correctly diagnose a ruptured Achilles’ tendon led to our client undergoing delayed reconstructive surgery two months after the initial injury.

This delay impacted the healing of his wound, resulting in him having to undergo a muscle and skin graft which left him with significant scarring. The man was a vulnerable adult and his injuries significantly impacted his mental health, causing him to experience a severe adjustment disorder with disturbance of emotions and conduct.

The claimant (C) was 40 years old when he was playing football in December 2013 and heard a crack from his ankle. The next day, he went to his local A&E department complaining of pain where he was briefly examined by a doctor and discharged.

After the New Year, he saw his GP with recurring ankle pain. He was diagnosed with a muscular-skeletal disorder, prescribed anti-inflammatory drug Naproxen, and given gentle exercises to do at home. Ten days later, C re-attended his GP who referred him to orthopaedics.

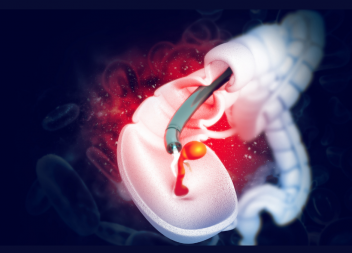

Here, he was told he’d ruptured his Achilles’ tendon and was put into an equinus cast to keep his foot in a downward position. He was told he needed surgery and was warned there was a small chance of wound problems due to the delay in diagnosis.

In mid-February 2014, he underwent Achilles’ tendon reconstruction. Post-surgery, his foot was placed in a non-weight bearing cast, which was swapped for a walker boot with heel wedges to start full weight bearing a month later.

However, he had developed wound problems with 2-3cm of his surgical cut having separated, or dehisced. He was seen in the plastics department and conservative wound treatment was recommended. But healing of the wound did not progress so, in April, he underwent a muscle graft to the Achilles tendon wound using tissue from the free gracilis muscle in his thigh, along with a split skin graft. He had to return to theatre the next day for a revision of the venous anastomosis attempted in his previous surgery.

By August 2014, the wound seemed to have healed; he was using silicone dressings and was referred for physiotherapy. By October 2014 he was advised to continue with scar therapy and was referred to the occupational therapy team for advice on compression garments and silicone. However, he continued to have significant functional problems with his right ankle due to the scarring.

The claimant sustained permanent injuries to his lower limb and brought a clinical negligence claim against the defendant, Leeds Teaching Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust alleging that it was negligent in failing to diagnose and treat the Achilles’ tendon rupture.

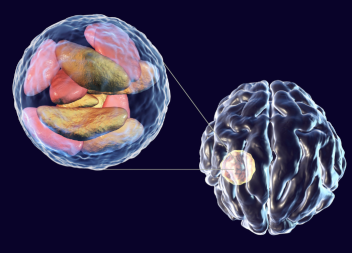

The defendant admitted breach of duty in failing to diagnose and treat the Achilles’ tendon rupture but disputed causation. It was C’s case that, but for the breach of duty, he would have elected for conservative treatment and avoided surgery and the resulting scarring and psychiatric injury.

Following mediation and various counter offers, the case eventually settled out of court at £225,000 total damages.